Product Description

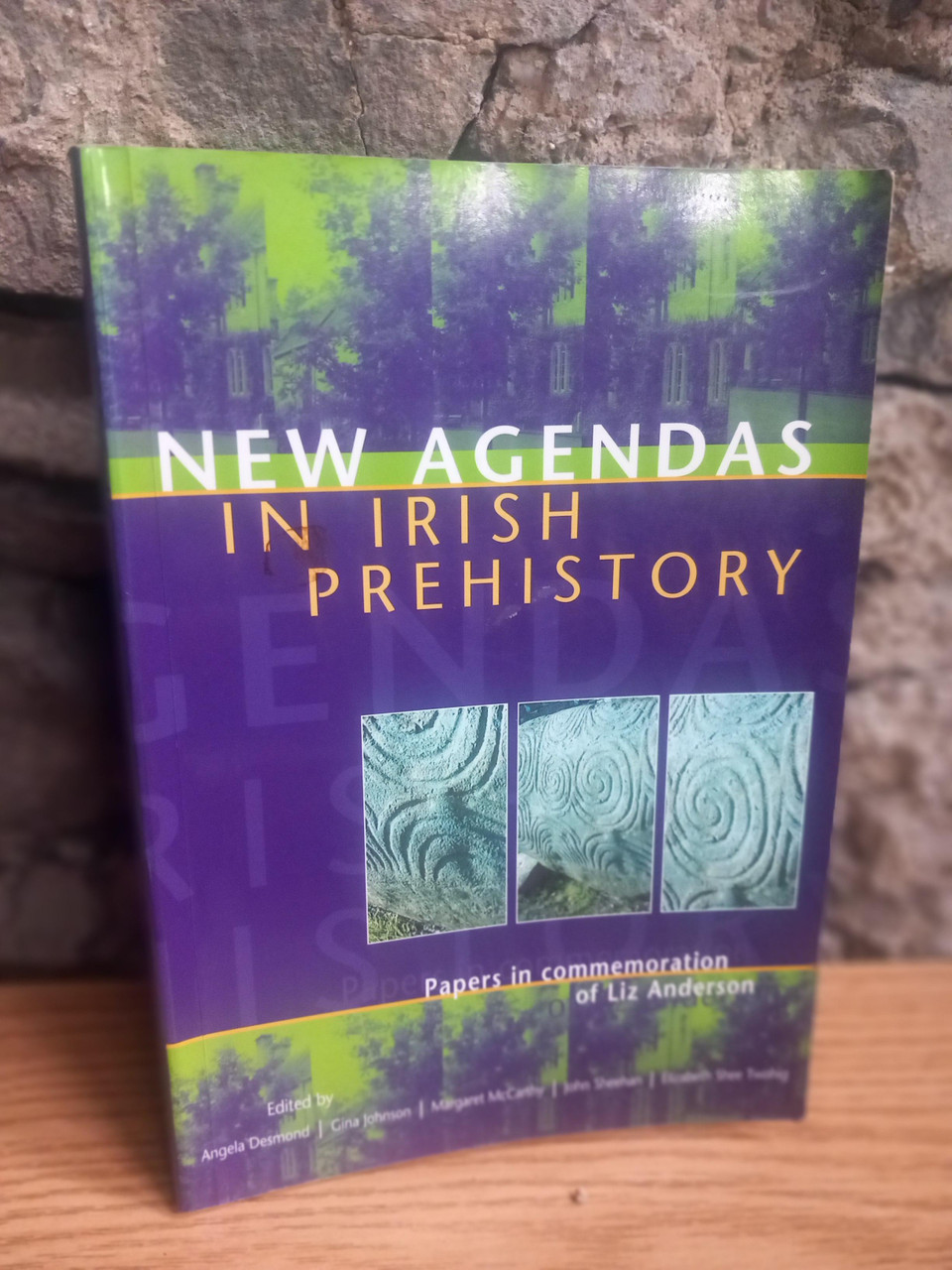

Essays and papers in commemoration of Liz Anderson.

Published by Wordwell, Dublin.

Represents the proceedings of a conference held in Cork in 1999 in memory of Liz Anderson. It comprises fifteen essays on various aspects of Irish prehistory which aim to 'identify and review a range of current problems in Irish prehistory'. Peter Woodman's opening contribution tackles the problem of 'new agendas' head on, by identifying what he sees as some of the most deep-rooted and insidious problems affecting the way Irish prehistory is studied. These include a rather too deferential attitude to the 'canon' of traditional thought which Woodman sees as hampering progress across the discipline. Like Cooney and Grogan, Woodman cites the problems of artificial period boundaries and monument/artefacts classifications which can prevent the identification of long-term processes and create circularity of argument. Similarly, the tendency to frame our questions in a rather narrow way (for example, to consider the appearance of La Tène art in terms of the 'origins of the Irish') leads to a certain insularity of approach. Instead Woodman suggests that we should be identifying those areas where the rich Irish data-sets can enable us to make contributions to archaeological problems on a European scale. Woodman also sees the tradition of typologically-driven research as responsible for the continued down-playing of those periods which lack characteristic suites of artefactual material (most critically perhaps the Later Mesolithic and Iron Age).

Several other contributions, such as those by Monk, Kimbal and Shee-Twohig, provide useful summaries of the state of play in various aspects of Irish prehistory, especially the Later Mesolithic and Neolithic. Others draw upon the mass of emerging data from recent rescue excavation to elucidate particular issues, e.g. Martin Doody's analysis of the evidence for Bronze Age houses. Elsewhere Maher and Sheehan present a comparative analysis of Dowris period and Viking hoards which raises some useful issues regarding the different assumptions applied to essentially similar data-sets by workers in different periods. In doing so they also provide a small but telling example of the potential benefits of breaking free from traditional period specialisation.

Of particular interest to this reviewer is Barra Ó Donnabháin's contribution on the thorny question of the Irish Iron Age. Much more than in Britain, the Irish Iron Age has long been dominated by questions of Celticity, specifically the 'coming of the Irish', and it is in this period that the inter-twining of contemporary politics and archaeological interpretation is at its most marked. The Celts have been used, for example, both to bolster colonial attitudes (Celts as incoming 'cultural improvers') and to proclaim an Irish identity in opposition to English colonialism (Celts as the original 'Irish'). Ó Donnabháin reviews the 'Celtic paradigm' in Ireland in the light of the recent vigorous debates over the existence and utility of the 'ancient Celts' (e.g. Megaw and Megaw 1996; James 1999). In his view, it is only with the establishment of alternatives to this Celtic paradigm that progress can be made in our understandings of this most elusive slice of Ireland's prehistory.

Questions of regionality are much to the fore throughout the volume, most notably in the contributions by Gabriel Cooney and Sinead McCartan, for the Neolithic and Mesolithic respectively. Both question the tendency to project modern perceptions of regionality, whether based on modern socio-political boundaries or perceived environmental 'zones', onto the prehistoric past. The striking divergence in Later Mesolithic chipped stone traditions either side of the North Channel, for example, seems to defy both the close geographical links and the marked cultural contacts of later times, such as the Neolithic or Early Historic periods.

The volume closes with a general review by John Coles, which echoes some of those issues raised by Woodman. In particular Coles laments the ways in which Ireland is often marginalised in wider accounts of European prehistory, reduced to a check-list of key sites, 'Mount Sandel, Newgrange and Knowth'. In Coles' view, the tendency to treat Irish prehistory as a purely Irish 'story' has been unhelpful in drawing out the wider potential of Ireland as a virtual island laboratory for the study of some of the key cultural transformations in Europe's prehistoric past.

The 'agendas' dealt with in this volume are predominantly academic ones, and there is relatively little coverage of issues relating to the more 'practical' agendas of data acquisition, management and dissemination. The exceptions are Denis Power's update on the work of the Archaeological Survey of Ireland and Caroline Wickham-Jones' discussion of her experiences of publishing on the Web. Given the publication crisis in Irish archaeology, which is perhaps the single most pressing issue facing the discipline (O'Sullivan 2001), this area might have been given rather more coverage. As John Coles points out, it is wonderful to see so much exciting new work unfold in the pages of Archaeology Ireland, but how many of these projects ever see anything approaching full publication? It might also have been useful to have had a rather wider overview of palaeoenvironmental issues, which surely must represent one of the most central areas of future research. There is nonetheless a good deal of important work here which will certainly push the debate further forwards.

Euro

Euro

British Pound

British Pound