Liam Cahill is a historian and writer. He has researched and studied the Limerick Soviet for many years and has written, lectured and broadcast on it widely – in Irish and English. The book, Forgotten Revolution is an expanded and completely revised edition of hs earlier book from 1990 of the same title. the book was launched in Limerick on 29th April 2019, almost 100 years to the day after the end of the Soviet.

The following is an extract from Liam's blog -

The October Revolution of 1917 in Russia sent shock waves across Europe and inspired the creation of soviets (or ‘workers’ councils’) in countries like Germany, Hungary and Italy. The Revolution, and the ideas that inspired it, had effects even as far away as Ireland.

In the city of Limerick, on May Day 1918, ten thousand workers gathered in the Market’s Field and declared: ‘We, the workers of Limerick and district, in mass meeting assembled, extend fraternal greetings to the workers of all countries, paying particular tribute to our Russian comrades who have waged such a magnificent struggle for their social and political emancipation.’

Irish workers were keen to embrace the new ideas and fashion them into a weapon for Irish freedom. This was consistent with the views of Marx, Engels and Lenin who saw Irish freedom as critical to the emancipation of the British working class and the demise of the Empire. It was aligned, too, with Connolly’s assertion that only the working class, organised into trade unions, could be relied upon to attain freedom for Irelan

Thus, a wave of small scale 'soviets' swept across Ireland from 1919 until 1923, beginning with a general strike of fourteen thousand workers in April 1919 in Limerick city, called by the local Trades and Labour Council.

Limerick

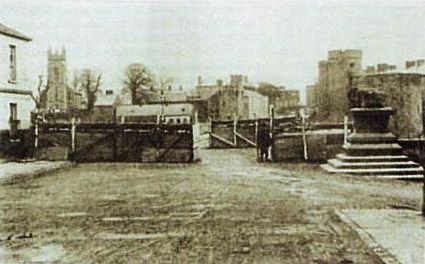

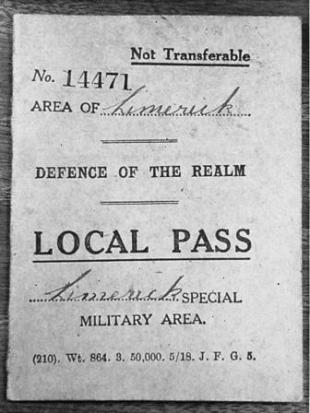

Robert Byrne was a leading IRB/IRA Volunteer and an active member of the Trades Council. After his conviction on an arms offence, he had been on hunger strike protesting against prison conditions and, in a botched rescue attempt in a local hospital,it was assumed that the RIC shot him. Responding to the daring IRB raid and to flush out IRA members hidden in the general population, the British authorities imposed a military pass system to check on workers going to and from their jobs - and placed barricades on the city's main bridges. This provoked the strike, which then evolved into a workers’ committee that governed the city for a fortnight.

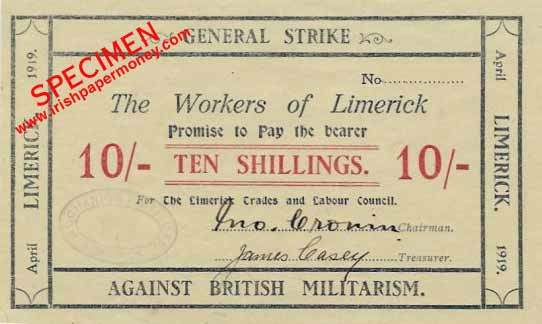

Sarcastically dubbed a ‘soviet’ by ‘The Irish Times’, the workerscontrolled the opening of bakeries, shops and distribution of food. They published their own newspaper ‘The Workers’ Bulletin’ and in a decision that marked the soviet as unique, they printed their own currency. The soviet achieved worldwide newspaper coverage and Dublin Castle feared it as a potential threat to their continued rule in Ireland.

After two weeks, the soviet faced a crisis. They had to either escalate the action nationally or face defeat. At the outset, they had the backing locally of the Catholic curates, Sinn Féin and the Volunteers. As the soviet evolved, they got strong words of support – but no action – from the national trade union leadership. The London executives of British-based unions – like the Railwaymen – were actively hostile. The Catholic bishops became opposed because of the threat of Soviet-style Communism and the Republicans because they feared the leadership of the coming struggle ebbing away from them

Initially, there was a partial resumption of work, then a full resumption after another week. Limerick ended in a ‘draw’ – neither a victory nor a total defeat for the local workers. In the end, the same forces that facilitated the creation of the Soviet at local level were the ones that turned against it when it looked like escalating into a general strike or a revolution against British rule in Ireland.

The Limerick workers had witnessed the practical example of up to eight localised general strikes in other Irish towns that had preceded their action. The first such strike took place in Youghal, county Cork, in December 1917. The local employers’ federation locked out all the unskilled workers in the town’s mills, stores and workshops in response to a wage claim by the National Union of Dock Labourers. After a week, the skilled tradesmen came out in sympathy and mass pickets were placed to prevent the movement of goods. Strikers and their supporters removed horses and drays from the employers’ yards and there were clashes with the RIC. After a fortnight, the strike was settled to the workers’ satisfaction. In the period August 1918 to April 1919, similar localised general strikes took place in Charleville, Ballina and Westport Graiguenamanagh, Killarney, Boyle, County Roscommon and Thurles, county Tipperary. None of these attained the degree of organisation of the Limerick strike but they were exemplars of what could be achieved by united action.

A lifelong trade unionist, Liam Cahill has held many representative positions in the Labour

movement from branch to national level and is a former Political Correspondent and

Economics Correspondent with RTÉ, Ireland’s public broadcaster. He has worked as a public

servant and as an adviser in government, politics, the private sector and with campaign

groups. For many years, he edited the popular web site ‘An Fear Rua – The GAA Unplugged’.

Liam was kind enough to sign copies of his book for us, and they are now available at https://thebookshop.ie/cahill-liam-forgotten-revolution-the-limerick-soviet-1919-signed-centenary-edition-2019/. The price includes tracked courier delivery within Ireland ( Northern Ireland and Republic) with GLS.

Euro

Euro

British Pound

British Pound