Product Description

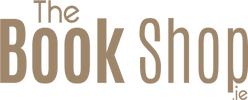

Hardcover , in glassine transparent jacket, as issued in a dark blue cardboard box with RAC emblem and the centenary dates on front box cover in silver.

As you grapple with increasing traffic, pollution and cities scarred by the motor car, it may be tempting to hark back to the golden age of transport, when stately horses and carriages plied the streets, and the air was as clear as a brisk autumn breeze. The Motoring Century: The Story of the Royal Automobile Club by Piers Brendon makes clear that this Arcadian view of our past was about as realistic as the notion that children were happier and our streets safer back in the good old Victorian days. They were nothing of the sort.

That cars would invariably be cleaner than horses was an Edwardian truism, supported by the likes of the Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, Rudyard Kipling (who described the horse as "the hairy enemy") and HG Wells. At the turn of the century, Britain had 3 million horses, each producing between three and four tons of dung a year. And as most lived in towns and cities, "a large town is really a colossal midden with houses dotted about in it", a journalist wrote in 1900. Horse-drawn vehicles were also far noisier than cars: the book notes "the extraordinary thunderous noise of the streets of London, when they were crammed with steel-wheeled horse-drawn vehicles rumbling and clattering over granite block paving".

This is not a pro-car tome, though. Rather it is an intelligent and fascinating story chronicling the social history of the car in Britain. As it was commissioned by the RAC, it deals in detail with that strange organisation that acts as national motoring organisation, governing body of British motor sport and Pall Mall social club.

Brendon says he was given a free hand to write a warts-and-all account of the car and of the club, and the book reads as such. Although the story ends on a bullish note for the RAC, throughout most of its history it comes across as a poorly managed, misogynous club for toffs, detached from the social mores of society. It resisted most compulsory speed limits, the breathalyser and the compulsory wearing of seat belts. In the early days, candidates were blackballed if they lacked the correct "background", were too obviously "in the trade", had a "common appearance", or "ran out of ditches". The club decided that "a working manager was not eligible for election". In the 1930s, a sign in the club read: "Members are requested not to bring undesirable women into the club unless they be wives or relatives of members." Ladies in trouser suits were not admitted until 1970. Even today, women cannot be full members of the Pall Mall Club or sit on the RAC board. And not that many years ago, the chairman's chauffeur "looked like a coachman and would only drive during the day because he could not see at night".

Brandon, whose previous works include Eminent Edwardians and Winston Churchill: A Brief Life, writes in a breezy yet authoritative style, which makes the book highly readable. His words are backed up by excellent photographs, the older ones being especially interesting. Brandon chronicles the growing Edwardian momentum for the motor car, but also recounts, in great detail, the resistance to it. Early cars "barked like a dog, and stank like a cat", and frightened rural populations. Charles Rolls, of Rolls-Royce fame, noted that, "every other man climbed up a tree or a telegraph pole to get out of your way; every woman ran away across the fields; every horse jumped over the garden wall".

Cars initially exacerbated Britain's already enormous class barriers, because only the wealthy could afford them. One MP commented that for the first time since the French Revolution the working class looked on the wealthy as "an intolerable nuisance". A poor man "did not like to be run over by a man of superior social position". The Marquess of Queensberry announced he would carry a loaded revolver, to shoot dangerous drivers. Some farmers, sick of dust storms caused by cars on gravel roads, suggested that cars be fitted with bombs that would explode when the driver pressed too hard on the accelerator. A wire was stretched over the Slough-Maidenhead road in an attempt to decapitate drivers. In the countryside, cars were frequently stoned.

Speed traps proliferated. Constables hid behind hedges using stopwatches, although some used church clocks. Most RAC members detested the traps, but the moderate majority was committed to reconciliation with the police. A more vociferous minority objected, accusing the club of "tasteful posturing and elegant inertia". They were determined to strike "a blow for automobilism as opposed to blind prejudice, crass ignorance and that form of highway robbery which masquerades under the title of `fines' for so-called excessive speed". In June 1905, that breakaway group formed its own club. The AA was born. Its sole purpose was to fight police traps.

The early days of motoring form the most fascinating part of the book, but Brendon also deals well with the 1920s and '30s, when cars such as the Austin Seven put Britain on wheels. Cars lost their social stigma; the middle classes were now motorised. But there were downsides. "Sunday churchgoing was the first casualty of the vehicle of freedom. Instead of attending a place of worship, middle-class motorists drove into the country, visited the seaside, picnicked at beauty spots or went off to play tennis

There was no denying the profound change caused by the car. "It transported the country to the city and vice versa. It finally snapped the fetters of locality. It helped to transform Britain from a congeries of regions into a united kingdom."

Euro

Euro

British Pound

British Pound